History

Historical Timeline

800-475 B.C.E

Period during the Archaic period

800–475 B.C.E

Many more tombs, larger spread from east to west

800–700/650 B.C.E

First use of Cypriot syllabic in Polis to write Greek

800–700/650 B.C.E

First multiroom structure preserved in B.D7 sanctuary

700/650–475 B.C.E

Marion develops a denser urban form, including an expansion of the sanctuary in Area B.D7, the earliest use of the sanctuary in Area A.H9, the “palace” in Areas B.F8 and B.F9, as well as structures in Area B.C6 in Peristeries, and buildings in Areas E.F2 and E.G0 in Petrerades

Early 7th cent. B.C.E

Earliest East Greek import

673/672 B.C.E

Earliest reference to Marion possibly as Nuria (in an inscription of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon)

Earliest evidence for bronze working in Polis

ca. 580 B.C.E

Earliest Attic imports

Development of Marion jugs with a woman holding a jug or a bull axed to the shoulder

Second half of the 6th cent. B.C.E

Egyptian imports

After ca. 520 B.C.E

Achaemenid import

Earliest Greek marble sculptural import

498–497 B.C.E

Possible destruction of Marion ca. 500 B.C.E during Ionian Revolt

After 500 B.C.E

A.H9 sanctuary possibly enlarged, B.D7 sanctuary of reduced scale

The Area

General Chronology for Cyprus

Earliest humans on Cyprus: ca. 10,000 BCE

Bronze Age: 3400-1050 BCE

Iron Age

Cypro-Geometric period: 1050-800

Marion

Cypro-Archaic period: 800-475 (Polis- Peristeries; B.F8/9 "PALACE")

Cypro-Archaic period: 800-475 (Polis-Peristeries; Sanctuary)

Cypro-Classical period: 475-310 (Polis-Maratheri; Temple)

Arsinoe

Hellenistic Period: 310-58 BCE (Polis-Petrerades; Public Building)

Roman Period/Early Roman: 58 BCE-330 CE

Byzantine

Late Antique/Late Antique: 330-649 CE (Polis-Petrerades; Basilica)

Byzantine: 649-1191 CE

Medieval: 1191-1571 CE

Polis Chrysochous

Ottoman: 1571-1878 CE

Modern: 1878-present

Princeton Cyprus Expedition

Past excavations done by Princeton in the areas of B.F8, B.F9, B.C6, and B.D7 unveiled a Cypro-Archaic public building, sanctuary, and some workshops as well as domestic structures. The dating of these archaeological remains date from the Geometric period all the way back to the early Cypro-Classical period.

Palace (B.F8/9)

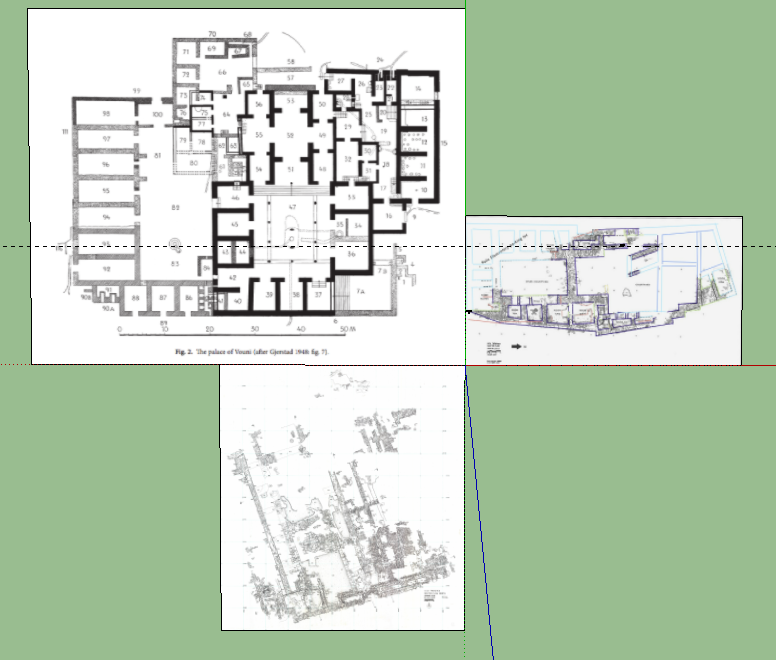

"It was over the course of the seventh century, and probably in its second half, that the city of Marion assumed a formal existence; until then, it has been proposed that the valley was a dependent of Paphos to the southwest. Around 600 b.c.e., it appears the whole site from east to west was gridded with a regular pattern of streets running north to south and east to west. On the southeastern edge of Peristeries, in Area B.F8/9, a substantial, and apparently secular structure was built employing large ashlar blocks in the lower walls and mud brick above, but the character of these walls can be convincingly visualized only by comparison with the preserved and impressive mud-brick foundation walls of Area E.G0. Although little pottery was collected from the rooms in Area B.F8/9, fragments of fine imported wares were found, and a small cistern produced almost complete local and imported storage vessels. These rooms around small courtyards, all with excellent concrete floors, probably served as the service wing of the building that stretched an unknown distance to the west under the recently constructed parking lot of the new elementary school. On the northern side of the building and at a slightly lower level was a series of rooms, the walls of which were made exclusively of rough stones. Here one room was filled with storage amphora and another had a small furnace for working metal, constituting a storage and craft wing. In view of the size and fine construction of the southern part of the building, it was nicknamed the "Palace." It seems likely that another prominent building existed in the western part of Marion since an impressive Hellenistic building in Area E.G0 reused a great number of ashlar limestone blocks, several with Cypriot syllabic mason's marks."

Tombs

"The general features of the tombs are standard: the tombs are dug into the sides of the hills or sunk deep in the ground with long entrance ramps, or as a dromo. The earlier tombs have a simple, single chamber that is roughly oval in shape. On occasion, there are niches in the dromos that probably originally held offerings to the dead; in some cases, they may have held small sculptures. The later tombs are frequently notable for their greater size and sometimes impressive architectural forms, such as rectangular plans, cut stone walls, moldings, and roofs in the form of barrel vaults, which suggests, as does so much else, a conspicuous prosperity in the later Classical period of the fourth century. The early tombs frequently held multiple burials interred over an extended period of time, but the early bodies and grave goods were simply pushed to the side to make room for the new arrival(s) with little or no decorum. Despite the size and wealth of the tombs, it appears that until the late fifth century there were no markers set over them to proclaim the name(s) and virtues of the deceased. Indeed, the graves of Marion reveal a rather special, not to say idiosyncratic, culture in the Chrysochou Valley that differed markedly from that of the other important centers on the island. The numerous small blocks of limestone, usually with only a name carved in Cypriot syllabary, were not used as visible markers above the tombs but have been found exclusively in the dromo or in the actual tomb chambers. In the late sixth century b.c.e., a very particular type of vase was also developed at Marion and remained popular into the fourth century: the one-handled jug or pitcher with one or more plastic figures on the shoulder. These, too, have been found almost exclusively in either the dromos or the tomb chamber."

Collections of tombs can be found both buried beneath the palace hill and across the palace on a neighboring hill. Tomb124A, which is the tomb found under the "Tomb" page was buried in the latter hill.

Sources: B.F8/9 Relationship to other Palaces

Expert of the site B.F8/9, Nassos--"emphasize[s] the extensive and solid usage of ashlar masonry types with close parallels in the nearby palace at Vouni. Likewise, equally impressive is the ample use of solidly constructed lime-base concrete for floors, a feature paralleled against Vouni, but also at Amathus and Idalion. Moreover, on the basis of the palace at Vouni it is possible that some of the eastern rooms were arranged around an open courtyard. In other words, we are here confronted with an extensive building complex, the main core of which was steadily built with state-of-the-art construction materials (ashlar blocks, concrete pavements, plastered walls) and techniques. It is therefore tempting to suggest that the massing of this building was intentionally calumnious and befits an architecture conceived to visually punctuate the material configuration of centralized power. To be sure, this structure lacks the sophistication in pan and construction of the palace at Vouni, or the evidence for storage of surplus or for manufacture of luxury products discovered at the Archaic palace of Amathus. Nevertheless, it is tempting to propose that it was a local seat of power, perhaps the seat of the dynasty that ruled the integrated state of Marion in the Archaic and Classical periods. This interpretation is certainly tentative, yet it underpinned by certain preliminary considerations regarding its actual and symbolic contexts and its structural sophistication"(Papalexandrou, 2006). Furthermore, the site was pillaged--and thus a lot of the ashlar blocks were robbed--this in turn has limited the amount of evidence avaible from the excavations.

Construction

Cyprus has fame for being a place in which the ground is filled with history; because of this, there is an ongoing battle between the Department of Antiquities and the residents of Cyprus. The Department of Antiquities serves as a method of preserving any ancient artifacts that are present in Cyprus. Because of this, the Department of Antiquities has found itself on multiple occasions as the barrier between an ancient history and a future construction that is highly dependent on monetary gains--thus, this has pushed for the future construction to at times be very alarming. Unfortunately, the site of B.F8/9 has been subject to damages because of the construction that has been attempted on the area before any preservation of the site could be accomplished.